TL;DR

- A meritocracy is a system where people receive rewards based on talent, effort, and achievement.

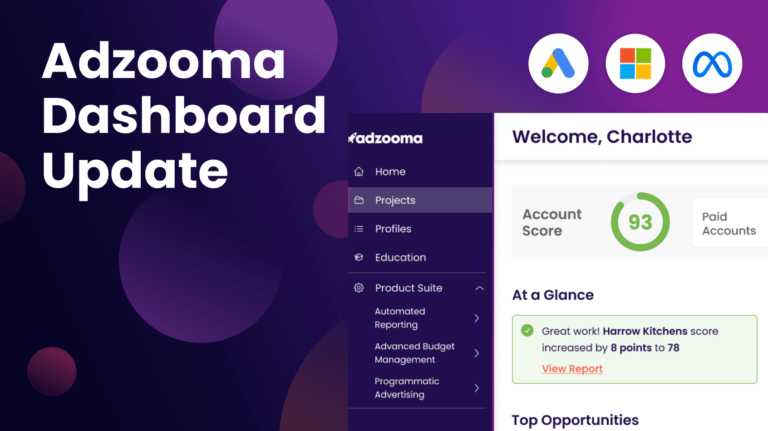

- Google Ads relies on a bidding system where users with PPC expertise perform better.

- There’s a mix bag of good and bad examples in the things Google as a company do.

- Google flits between both forms of meritocracy: classical and modern.

- But the definition of merit and who can earn it isn’t always equal causing inconsistent policies.

Disclaimer: The opinions and beliefs expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the policies of Adzooma or the viewpoints of any other employees.

Sally Ride – the first American woman to enter space – studied there. Tiger Woods went on a golf scholarship there. And John F Kennedy dropped out of their MBA program. What institution am I talking about? Stanford University.

A world leader in research, Stanford has a strong relationship with Silicon Valley and Google’s founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin both studied there in the 1990s. In Room 360 of the Gates Computer Science Building, Larry Page worked on his PhD in computer science and with the help of colleague Sean Anderson came up with a new name for their search engine. It was originally named BackRub, in reference to the search engine’s “back link” analysis but with a few typo-related tweaks, BackRub became Google (at least officially) in September 1998.

Google celebrated its 21st birthday last month and to call its rise “meteoric” would be an understatement, a cliche, and a pun all in one. Innovation runs through the veins of the company. Google’s influence on technology and society’s relationship with the internet is unfathomable in the 3 decades of its existence. But with that success comes a lot of responsibility, both to its employees and its users.

Questions have been raised about Google’s involvement with spreading misinformation during the 2016 US presidential election as well as controversy surrounding pay and accusations of censorship.

But with all its algorithms and eerily-accurate machine learning, is Google a meritocracy or another technoligarchy like Amazon and Apple?

What is a meritocracy anyway?

Before I can discuss Google in the context of power, it’s necessary to define what a meritocracy is.

A meritocracy is a system where people receive rewards based on talent, effort, and achievement. This differs from, say, nepotism, where people are rewarded for their relationships to those in power.

Our world runs on the idea of meritocracy. From early childhood, we take standardised tests to progress through education. Work hard and you’ll get what you deserve.

For Google, that is evident in its search engine ranking structure. Google Ads relies on bidding for space at the top of search engine results pages. The more talented users with PPC advertising knowledge and expertise perform better. Ranking organically also takes skill and that’s why we have search engine optimisation.

The good in Google

Google continues to do a lot of good for the world. Here are some examples.

Google.org’s data-driven philanthropy

In 2005, Google launched Google.org to provide grants to charities. Thanks to its technology and data, Google.org has funded initiatives in racial equality in the United States, education, equality for disabled people, social crises like the Ebola crisis in 2014, and the Nepal earthquake in 2015.

January saw the company’s launch of the Google.org Fellowship where employees were allocated up to 6 months of full-time pro bono work. The different projects echoed Google.org’s core beliefs in improving areas like education and criminal justice.AI for social good. There are a lot of challenges facing the world, socially and ecologically. AI can help with that and thanks to Google’s AI for Social Good, it’s making positive contributions.

Google.org heads the Google AI Impact Challenge with a $25M pool for 20 organisations over 6 continents. But what can AI really do for the planet? Take a look at some of the projects. It has helped marine biologists protect the ocean’s ecosystem, helped medical professionals in predicting heart attacks, and forecasted floods with better predictive models.

Positive work in health and medicine

Google has also found ways to improve worldwide health as well as innovating the field of medicine.

- Annually, influenza has caused up to 49 million illnesses and 79,000 deaths in the US alone. Until 2014, Google Flu Trends calculated estimates of flu outbreaks based on search patterns.

- Google Fit launched in 2014 in conjunction with the World Health Organization. It provides fitness coaching and measurable goals to improve fitness, reduce the risk of heart disease, and improve mental health and sleep.

- Google Glass helped surgeons with surgical procedures between 2013 and 2014, demonstrating the technology’s capabilities.

- In 2018, Google’s Deep Mind identified dozens of diseases and showed how it came to those diagnoses. A study published in Nature Medicine described the safety of AI in diagnosis and treatment recommendations for vision problems to cancer.

Google has shown its capabilities in modern medicine and ways to shape medicine in the future.

Web and social accessibility

The Web should be for everyone. But for millions around the world, internet access is difficult or non-existent. And for those in education, the lack of access to valuable resources hampers progression. That doesn’t bode well for a system based on meritocratic ideals.

Google has worked hard to bridge those gaps, both in social and web accessibility. The company works with institutions and charities to support learning from primary school to university. The Google Cloud Platform aids research and access to learning materials alongside the dedicated G Suite for Education, while Google Chromebooks give students and teachers a great way to collaborate and learn. G Suite is also free, making it a cost-effective platform compared to Microsoft Office.

For web accessibility, Google has created resources for web developers as well as customers to help provide the best environment for everyone. Google are also members of a variety of accessible web initiatives including the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), a series of guidelines for improving web accessibility, and their own Google Impact Challenge: Disabilities, which aims to make the world more accessible for the millions of disabled people around the world.

Google’s promotion of local journalism

Google holds a lot of power when it comes to news. While there have been questions about the amount of power it has (more on that later), the tech giant has made steps to redress any imbalance.

In September 2019, Google teamed with Archant to fund a project called Project Neon. The partnership will result in three news websites “underserved by local news”. The project will last for three years and comes after a successful Google-funded project in 2017 – Local Recall – where 150 years of archives were digitised for local communities.

Google’s news search algorithms have also been improved to avoid syndicated content from ranking above original news. To do so, a large team of human reviewers will provide feedback and ensure new stories are prioritised over syndicated news.

PageRank and fighting the spammers

Speaking of algorithms, PageRank is one of the most important to the foundations of Google as a search engine and business. PageRank measures the importance of web pages based on the number and quality of backlinks to them. Then, it calculates an estimated importance “rank”.

This helps search engine users by giving them the most relevant articles first. There are other factors that help calculate a page’s relevance but the idea is the more authoritative sites linking to your site, the better. This also means spam sites don’t reach the top. Another measure to combat spam sites is the nofollow attribute where Google ignores links using this code.

Is Google evil?

As corporate mottos go, “don’t be evil” is deep but what does it really mean? (I won’t give a definition of evil as I’m not a priest and this isn’t a theology dissertation.)

Technically, “don’t be evil” is now a phrase in Google’s very own code of conduct but its message has been obscured.

Don’t be evil. We believe strongly that in the long term, we will be better served—as shareholders and in all other ways—by a company that does good things for the world even if we forgo some short term gains. This is an important aspect of our culture and is broadly shared within the company.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin, 2004

But in a 2013 interview, former CEO Eric Schmidt said he thought it was “the stupidest rule ever” after the pair announced the motto. He later changed his mind after a subsequent meeting.

The line was then altered to say “You can make money without doing evil”. Was it more specific or had the company’s focus shifted towards making money?

Here are a few instances of Google’s questionable decisions in recent times.

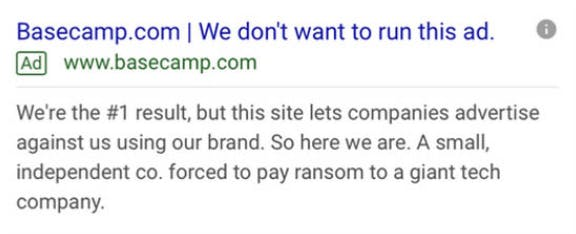

Competitor brand bidding on Google Ads

Let’s look at the facts. Google Ads is an online advertising platform. Publishers pay to display their ads on Google’s network. That involves bidding on certain keywords. Competitor keywords aren’t reserved to those competitors.

But that hasn’t stopped an uproar over competitor brand bidding. Basecamp is a project management company in Chicago and ran a controversial ad in response to competitors bidding on the “basecamp” keyword.

Is it fair to allow competitors to bid on your brand’s name? The debate storm swirled onto Twitter and the response was mixed.

Interestingly, Tim Soulo, the author of that Twitter thread is a colleague of Dmitry Gerasimenko at Ahrefs who said “no one should ‘own’ something meant for the good of all.” If Google as a transparent search engine is to serve a response to search intent, it has to keep keywords open to all. But that hasn’t always been the case (as we’ll see later) and it’s a tricky subject, both morally and economically.

Google’s tax avoidance

Paying little-to-no tax isn’t Google-specific but in an age of “tax-shaming”, it’s not a good look.

In January 2019, documents filed at the Dutch Chamber of Commerce claimed Google had moved €19.9bn through a Dutch shell company to Bermuda in 2017. The transfer was part of an arrangement, known as “double Irish, Dutch sandwich”, to reduce its foreign tax bill. The legality of the act won’t make a difference to those who believe corporations should pay their fair share.

While still a legal practice, it will be completely phased out in 2020. Whether Google will pay their outstanding tax or use alternative methods to evade is another question.

Google’s effect on local journalism

I discussed Google’s financial assistance to local journalism earlier. But many in the industry have questioned the company’s motives.

For the Wall Street Journal, Lukas I. Alpert wrote that Google – along with Facebook – was “making concessions long sought by news publishers whose business has been hurt by the platforms’ dominance”. The claim was that Google was diverting negative attention from the regulators, rather than helping news outlets out of goodwill.

US law officials launched antitrust investigations into both companies to see whether their online dominance was anti-competition. A meeting is set to take place in November in Colorado.

SERP features and the power of search real estate

Another debate amongst the digital marketing industry is how much of Google’s SERPs are actually Google’s products.

SERP features occupy more space than a standard organic listing and come in different formats. Because of their size, they push listings down the page (even further if a SERP includes four ads at the top). Some SERP features scrape content from the pages with information that answers the search query. This sometimes leads to no clicks on pages being scraped.

Earlier in the year, SparkToro conducted a study with startling results. It concluded that 48.96% of those searches resulted in no clicks for Q1 and 6.01% of all searches went to websites owned by Alphabet (Google’s parent company).

Music lyrics website Genius.com also caught Google out for scraping data. Is this fair to web publishers? Some say not. Google employees have suggested they are in the business of giving answers to questions and that’s exactly what they’re doing.

The nofollow change: from rule to hint

The nofollow attribute was introduced to prevent spammers gaining ranking advantages in the SERPs. In time, high-authority sites started using them to prevent link juice being passed to lower-authority sites, regardless of quality.

Because of how the Google search algorithm works, influential sites linking to newer sites can damage their SEO. Inversely, newer sites are recommended to link to high-authority sites to boost their SEO. This doesn’t sound great: smaller sites must give bigger sites the boost but not the other way around. How are they expected to grow in the same way?

In September 2019, Google announced a change to the nofollow attribute – it would be a “hint” rather than a rule. That meant Google could choose to ignore it altogether. No more blanket nofollow links. But it doesn’t have to be implemented and there are no penalties if you don’t. So where is the motivation to use it?

Of course, SEOs went into a frenzy over what it all meant and a myriad of questions were asked. Not all questions had clear-cut answers and some were simply “did you read the article?”. Why propose a significant change in an industry full of best guesses with unclear intentions and optional use? Wouldn’t it have been better to just leave everything as it was? See? Yet more questions.

The Google memo

Remember James Damore? He was the former Google engineer who wrote “Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber”. In it, Damore argued that women were underrepresented in tech because of psychological differences between men and women. After it leaked, he was sacked and later tried to sue Google for “discriminating against conservative white men”. He eventually dropped the case. Google’s Vice President of Diversity, Integrity & Governance Danielle Brown issued her own memo and CEO Sundar Pichai wrote a supporting statement which said while Damore’s comments were not okay, neither was the fear to express similar opinions or debate them.

Damore was officially sacked for violating Google’s code of conduct. But there’s a contradiction in what happened and what was subsequently said. Did his rhetoric play a part in his dismissal? And if it’s okay to express and debate these topics, then why wasn’t he just suspended?

I strongly disagree with the memo and its contents but as a company, you should be transparent in what you stand for and not make statements that contradict your actions.

The Medic update and YMYL

In August 2018, Google rolled out a core update that sent shockwaves through a lot of sites’ rankings. Due to its significant effect on a number of health sites, Barry Schwartz dubbed it the “medic” update.

A growing number of medical e-commerce sites affected related to YMYL (Your Money or Your Life), an ideal that safeguarded users from potentially harmful content that affected their lives or their money. This included pages providing information or advice about health, drugs, medical conditions, mental health etc.

The Medic update didn’t single out health sites for ranking drops and targeting websites selling products with no scientific backing isn’t a good thing. But it doesn’t always work out.

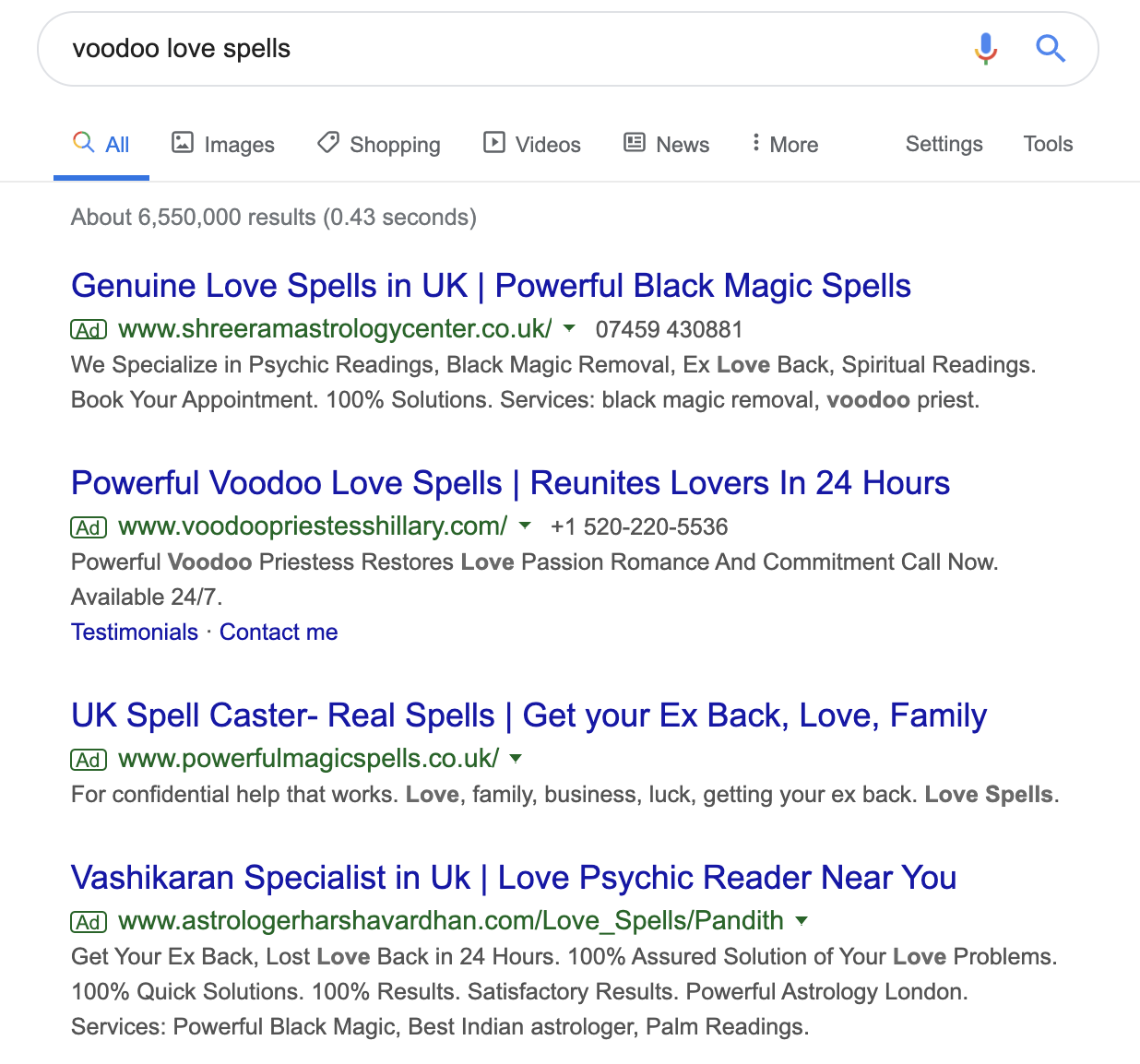

Observe this advert on Google:

“Genuine” voodoo love spells? The NHS would beg to differ.

Not one but four ads served for a magic spell. Isn’t this what YMYL is meant to extinguish? Google Ads has made a lot of changes to usher in an age of machine learning to automate the ads you see and create. This should have been picked up quite easily as it’s about your money and your life. Maybe an abracadabra will make it disappear, who knows.

Google and surveillance capitalism

Shoshana Zuboff’s book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power is an exposé into the concept of commodifying personal information. Zuboff popularised the term surveillance capitalism and Google – along with Facebook again – take centre stage in her critique.

For Zuboff, who discussed her book in a January article with The Guardian, Google pioneered surveillance capitalism. She claimed the company uses it to dominate human experiences in an age of “information capitalism.” From Google’s ill-fated attempt to digitise every book in the history of print to photographing every nook and cranny of the outdoor world for Google Maps, she claims Google knows what it is doing and it uses user data to control and surveil us.

This might come across as the musings of a conspiracy theorist but it’s not far from what we can immediately test.

Google Autocomplete doesn’t guess what you’re about to type. It’s based on behavioural data and everything you’ve typed before. It makes predictions and they’re often very close if not spot on. Then there’s Google’s pioneering work with machine learning. And have you ever wondered how the ads you seem frighteningly related to things you discovered offline? At least Google Earth isn’t flat.

Are meritocracies a corporate myth?

I gave a brief definition of what a meritocracy was at the start of this article. But I left out a salient part: it was originally a satirical term.

In 1958, British sociologist Michael Dunlop Young wrote The Rise of the Meritocracy about a future British society where merit superseded the class system we know today. Since hard work was the way to get ahead, the fictional meritocracy replaced regular democracy.

The book gained popularity as did the term. But the satirical meaning didn’t transfer over and meritocracy became a positive term.

But are meritocracies real? Can everyone get ahead purely based on hard work and merit? Statistics disagree. A study by Hired called The State of Wage Inequality in the Workplace found:

- Men were offered more for the same role at the same company 60% of the time

- 61% of women felt discriminated against in the workplace

- For every $1 earned by a white man, black men and women earn $0.90 on average

And that’s just looking at cis men and women. LGBTQ+ men and women earn less than their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts too.

Google has a specific diversity program and publishes an annual diversity report. 2019’s report showed increases in areas but also decreases, such as an 11.9% reduction in female hires in “organisational leadership hires” between 2017 and 2018 (as discussed by Forbes).

The truth is Google flits between both forms of meritocracy: classical and modern. But the definition of merit and who can earn it isn’t always equal and that leads to inconsistency when it comes to enacting policies. Google isn’t evil but it is highly placed in a hyper-capitalist system.

And the biggest irony for Google is the precarious position it regularly finds itself in – thanks to a mix of academic merit and a small typo in a shared office in Gates Computer Science Building, California.